|

[image description: a simple chalk drawing of a rainbow on rough, dark grey concrete]

Autistic people should be self-determined in choosing labels and identifiers that feel right to us and that reflect our understanding of ourselves within our cultures, communities, and the world. Autistic people should also be helped to understand that the labels we choose can communicate information about our individual ethics. The Asperger’s label is being abandoned globally. There are autistic adults who identify strongly with this label, or variations such as “aspie” or “aspergian”. Right now, this topic is the subject of heated discussion in the Autistic Community. I am an adult who was diagnosed with autism back when Asperger’s syndrome was still in the DSM. I was also an early, precocious talker who did-not have co-occurring conditions present in childhood, and a different psychologist may have chosen an Asperger’s diagnosis for me. My four year old child, however, would never have been considered for a designation of Asperger's. He is non-speaking, with very high adaptive support needs. I have no grief over my child’s presentation of autism, and I never have. He is funny, charming, persistent, affectionate, easy going, curious, sassy, and interesting. I love him because he’s my kiddo, but I also like him very much. I enjoy spending time with him, I like what he’s added to our family, and I wouldn’t change a thing about his neurology. One of the coolest things about being an autistic parent of autistic kids is getting to welcome them to our community. Being part of a multigenerational Autistic Community is an incredible experience, and we are lucky to have a thriving local one that we engage with on and offline. We also have the greater, global Autistic Community, and passing this legacy down to my children is a privilege I am thankful to have, a privilege past generations of autists were not generally able to access. When members of these communities use the label “Asperger’s” to identify themselves, my stomach tightens a little. I try to assume good intentions and ask neutral, exploratory questions about their choice. Every once in awhile, the person is very new to autism, and Asperger’s is the label a clinician gave them, and they don’t really know much more than that. However, that’s usually not the case. Not here in the United States, where Asperger’s hasn’t been widely diagnosed in more than half a decade. Usually the questions lead to predictable answers like:

I want to unpack these answers. It’s true that there are different presentations of autism, but it’s untrue that there are just two presentations of autism, called autism and Asperger’s. Every person who identifies with the Asperger’s label does not have the exact same presentation of autism, that’s just silly. So, when people say they specifically identify with the “Asperger’s presentation” of autism over the “Autistic presentation”, what does that mean? That they identify with autistics who have communication differences? Nope, that’s all of us. Social differences? All of us. Differences in processing information and sensory stimulus? All of us. Difficulties with executive function and emotional regulation? All. Of. Us. So what is this “Aspie presentation”? Here’s what people won’t say. Asperger’s is socially understood as autism, but you’re smart and you can talk. Being “smart” (having average to high IQ) and being able to prove your intelligence in typical ways is valued and privileged in mainstream culture. Being able to communicate in the most typical way—by speaking with your mouth—is valued and privileged in mainstream culture. Use of the Asperger’s label communicates that a person wants their neurodivergence acknowledged, but wants to signal that they’re more valuable then other autistics, and they want to take full advantage of any privilege available to them within a harmful hierarchy of disabled humanity and worth. It is very possible for people to use this label without understanding that this is what the label communicates. The impact can occur without the intention. You might be reading this, thinking, “I use Asperger’s, and I definitely don’t feel this way.” Okay. But, please take a moment to consider what about the label “Autistic” is difficult for you to identify with. Write down your answers. Think about your answers. Then reread the three paragraphs above. See if anything shifts. As for “helps me find people like me”, I’m not even totally sure what that means. It doesn’t seem to mean people of the same age, gender, geographic area. It also doesn’t seem to mean people with the same interests, or who enjoy the same activities. It can’t mean people with sensory, executive function, social, communication, or emotional regulation differences (cuz that’s All. Of. Us. No need for the Asperger’s label for that). Again, what “people like me” seems to mean is “people who have a similar IQ to me, who can demonstrate their IQ in typical ways like I can, and can communicate at the same speed and with the same complexity as me using modes I’m already familiar with”. Why is it important to have a way to meet people with these qualities? Why is it important to have a word that means, “looking for friends, those with intellectual disabilities need not apply”? Why is it important to have a signal that means “I have a complex vocabulary, and I’m not interested in communicating regularly with people who have access to less vocabulary”? When people use the label Asperger’s to “find people like me”, what they seem to mean is that they don’t really want to socialize with autistics who have co-occurring ID, significant motor planning impairments, and/or complex communication needs. *Some* disabled people make suitable friends and conversation partners, but some *other* disabled folks are just not palatable, or are too difficult to engage. I have heard people who use the label “Asperger's” say that this label was their access point to autism, that pre-diagnosis they had so many misconceptions of autism that they never would have investigated it or considered that they could be autistic. Fair enough. However, this is a problem. It is a problem that autism is so poorly understood that actual autistics don’t even know what it is or that autism could be their neurotype. The solution to this problem is not to promote continued use of the Asperger’s label as an access point. Offering a “less scary” presentation of autism as a way to help people feel comfortable accessing the Autism Community relies on there being a “more scary” presentation, and increases stigma and oppression for those with the “more scary” presentation. That’s not an acceptable trade off. I have also heard people who use the label “Asperger’s” say they find it useful to communicate about the difficulties of being high masking with other high masking folks, and that they experience solidarity with other autistic people who are underserved because their support needs aren’t recognized or understood. I think these are important and worthwhile points of connection. I don’t believe they must take place in groups or spaces that center Asperger’s or rely on that designation. They can occur in spaces for all autistics. A post about masking will attract people who want to talk about masking. A blog post about lack of services for autists who live independently will be shared and read by those who relate to the content. The Asperger's label is not necessary to facilitate conversations or information sharing on these topics. I am raising an autistic child with big support needs who requires a lot of communication support across multiple modes of communication. He deserves a place in our community. I don’t like knowing that there are members in our community who see their autism as so different from his it needs a separate label. I don’t like that there are members in our community who use that label to define spaces that are not for him. I don’t like that there are people in our community who think my child’s neurology is so bad, so shameful, that they hold on to a diagnosis that either no longer exists or soon will not, all so nobody mistakes them as being like him. You are like my child. My child is like you. I’m proud to share a diagnosis with my child. Are you?

4 Comments

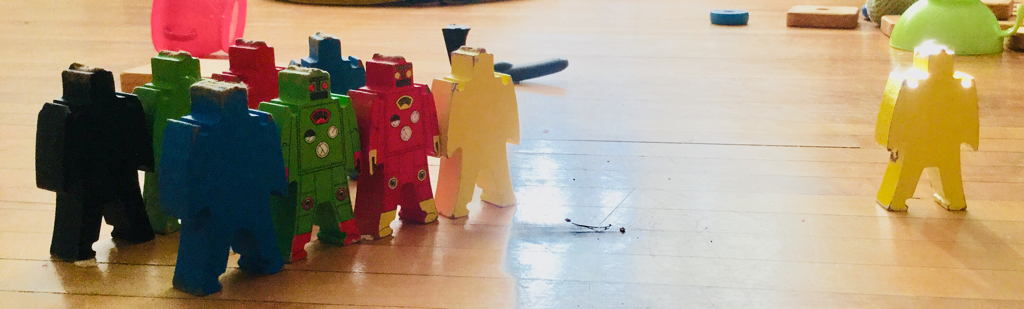

[Image is paragraph on paper that says “Pre-Linguistic Communication Long Term Goal: ST LTG #2 To increase his pre-linguistic communication skills, (name blocked out) will show shared enjoyment, seek people over objects, manipulate toys symbolically, respond to his name, come up with 4 new ideas within several play schemes, participate in 30 circles of communication, respond to route and 1-step novel directions and imitate what he sees other people doing within play and songs as observed by his speech therpists and paretns by June of 2019”.]

I’m going to break down a piece of a medical document of my child’s—a speech goal—hoping it’s helpful. I don’t take sharing medical documents lightly, but In this case I don’t think I’m violating his privacy or dignity, I’d be comfortable with him seeing and reading this in the future, and I think there’s a really important teachable moment in these few lines. This goal was created by a private speech therapist who briefly treated my child. The facility this occurred at does not use any form of ABA in any of their services. I vetted them extensively prior to allowing my child to receive services. I was very transparent and direct about the fact that we did not want any neuronormative goals (goals that were related to him acting less autistic or preforming as NT). They were enthusiastic about working with us. Great! I did my due diligence, right? The above goal was found in his treatment plan. By the time I received it, we’d already pulled him from the program based on a clinical observation of his therapy, and not being comfortable with their strategies. Lets unpack. -Show shared enjoyment. Foxy was already a happy flapper when evaluated. He was already showing shared enjoyment autistically by jumping up and down and flapping his hands. If you see this in your child’s plan, it probably means they want to increase normative enjoyment behavior. -Seek people over objects. Autistic people are bottom up processors who often learn best by interacting with materials instead of people. We can go at our own pace and take as much time as we need to process, and there aren’t social demands stressing us out while we’re trying to learn new stuff. This goal means they want to train your kid to learn and socialize more like an NT kid, instead of working with their inherent strengths like implicit learning and being detail oriented. -Manipulate toys symbolically. This literally means “play with toys like an NT kid”. Using them “imaginatively” as symbols representing a real object. The toy car represents a real car, so you pretend to drive it. The baby doll represents a real baby, so you feed it. You do not line toys up, sort and organize them, spin the car wheels, or rub the doll’s hair against your cheek. That is not symbolic play. -Participate in 30 circles of communication. I written about this before, but in short, communication in any mode can be very effortful for autistics. We need people to respect that communication can be overwhelming and exhausting for us. Taking turns in communication is also really hard to figure out. Ask any autistic about the mental gymnastics involved in figuring out when its our turn to talk and when it’s the other person’s turn. 30 circles of communication is 30 “turns” in a single interaction. Requiring an autistic child to communicate more, with increased turns, just for the sake of more turns is imposing NT communication styles. It is saying you want the child to communicate more normatively. It is different from wanting to help a child to be able to access more language so they can express themselves. It is trying to get them to express themselves more like an NT kid. Pay attention. Most providers—even very good, very skilled, non-ABA providers—are not going to grasp that they are trying to get your autistic kid to act less autistic and why that might not be what’s best for them. A good question for a perspective therapist is, “Do you consult with autistic adults?” Over the past ten years in the United States, there has been a significant increase in early identification of disabilities that may impact the educational needs of children. One positive impact of increased early identification is that more students are accessing their federal right to an IEP. Autistic kids in particular are recieving this needed educational support in greater numbers. Unfortuately, increased access may not be enough. How can we better meet the needs of autistic children in our public school system?

One method in current practice is placing autistic children in inclusive, general education classrooms. For all members and facets of society, inclusion is a vital human right. It can be difficult at times, however, to conceptualize valuing educational inclusion of disabled students the same way we value other forms of inclusion, because it seems to exist at odds with the educational needs of all students, both disabled and nondisabled. It’s crucial that we imagine and innovate fresh, creative designs and methods for inclusive classrooms that provide equal educational benefit to all children. Autistic children learn differently than their allistic peers. Often, autistic students benefit from learning components prior to process, multi-modal presentation of material, and opportunities for implicit learning. Flexibility in teaching modalities can help all students reach their individual potentials. Peer mediated teaching, and creating classroom curriculum that draws from an autistic student’s area(s) of interest can both support autistic students in learning the material and provide opportunities for social inclusion. Sensory regulation benefits everyone, and many sensory supports can be pushed in for spontanious use by all students, abandoning assigned desk seating and adopting freedom of movement to meet sensory needs classroom-wide. Direct, general education about sensory regulation and forms of sensory input can significantly decrease behavioral difficulties for all students, autistic or not, and promote inclusion rather than singling an autistic student out. All teachers need and deserve training for these types of strategies. Consideration of a classroom aide instead of a 1:1 para may be appropriate in many IEPs. A classroom aide mitigates the profiling experienced by some disabled students because of the presense of a 1:1. A classroom aide can facilitate inclusion in a much more generalized way than a 1:1 para. Development of the position “Classroom Inclusion Aide”, with defined training and continuing education on the implementation of new methods of inclusion—particularly those developed by autistic and other neurodivergent people—would be the best use of that resource. Autistic students can be placed in inclusive classrooms even if they are not demonstating the same kind of knowledge on the same subjects as their typically developing peers. Autistic learning is most often compartmentalized instead of linear, with long incubations before skill mastery is demonstrated. Very often, progress is internal. Presumption of competence and information presentation using multiple modes benefit all students. As we are all sadly aware, many nondisabled students are not making sufficient educational progress either, and nondisabled students are also communicating unmet needs with behaviors. Stratagy shifts that show promise for better student support across abilities must be prioritized. Increasing multi-modal teaching and decreasing testing—instead measuring progress by observation over a long data collection period—would allow autistic students to be placed in classrooms with their same age allistic peers more often, with greater success for all students. There is an adage that goes, “If you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always get what you’ve always got”. It’s time to accept the idea that inserting a special ed classroom of one into a general education classroom is not inclusion. It’s preformance of inclusion, and it’s not working well for anyone. The truly inclusive public school classroom may yet need to be invented. I have shared just a handful of possible inclusion stratagies; there are many more to be imagined. The inclusive classroom, by definition, will equaly meet the needs of all students, leaving no one behind. When Foxy was being evaluated by our public school system for a trail with a high tech communication device, I had to answer a lot of questions about his communication skills at the time.

For the most part, this was not too difficult. As an autistic person, answering specific questions is one of the easiest ways for me to communicate information, and all the better when I’m passionate about the subject matter. I am very passionate about both my child, and communication. However, I got stumped by one question. Can he participate in turn taking while communicating? I wasn’t stumped because I didn’t know whether or not Foxy had that skill. I was stumped because I didn’t understand what the evaluator meant. “What do you mean by turn taking while communicating?” I asked. The evaluator tried to explain it to me. I still didn’t get it. Foxy’s special education teacher, who knew me better than the evaluator, also tried. No dice. Finally I looked at my partner, Mischa, who knows me very, very well and has a good grasp on how autism impacts my communication. He tried to explain it. Nope. Nothing. Crickets. An autistic blind spot had revealed itself. And now, having used up so much energy trying to understand this neurotypical social ritual, I was irritated and confused and no longer able to effectively advocate for my kid. I’m lucky my partner and his early intervention team were able to complete the effort and get the trial I wanted. Which illustrates a really important concept: many regular old neurotypical social routines are not accessable to autistics. Trying to access them feels frustrating, defeating, and really wears us out. Recently, a speech therapist who evaluated Foxy for private therapy services set a long term goal of participation in “30 circles of communication”. I remembered reading about circles of communication in Erin Human’s valuable critique of D.I.R/Floortime. I revisited that piece and something clicked in my brain. “Circles of communication” was the same thing as “turn taking while communicating”. It’s like volley ball. This therapist wanted Foxy to be able to keep the communication ball going until it had traveled over the net 30 times, to expand the number of “turns” in a single interaction significantly. Here’s an example: a child points to a toy robot on a shelf. His mom takes it down and hands it to him. He runs off to play with the robot, ending the interaction. There was only one turn. The communication ball only went over the net once, from child to mother. Also, no words were used, just gestures. Or, a child points to a toy robot on a shelf. Mom says, “hmmm, you’re pointing at something, but I don’t know what it is. Can you tell me?” (She knows it’s the robot, she’s just trying to create opportunities for more circles of communication.) The child might make a vocalization now. In response, Mom picks up a container of blocks, and playfully asks, “Did you say you wanted these blocks?” Child shakes his head no, laughing. Mom says, “No? Not the blocks? Maybe you want your...school bus puzzle!” She shows the puzzle to him. Child giggles and says, “Nnnnn. Wo! Wo!” “Oh! you want your robot! Can you say robot?” Child, “Wo!” Mom, “What? I couldn’t quite understand?” Child, “WO! WO!” Mom, “Great job! Robot! Okay, let’s get your robot down. Where should we play with him?” Child runs to a corner of the room and looks at mom expectantly. Mom says, “Over there? Okay! Here we come!” That was twelve circles of communication, and included both gestures and words. Turn taking in communication is a neurotypical developmental milestone. Expanding circles of communication is a neurotypical social goal. Trying to make autistic children do this is a disservice. Our brains are different. We have different strengths and abilities that really should be nutured and supported so that we can reach our full potential. We have Economy* of Turn Taking. That means, we are geared towards figuring out how to communicate all the required information using the fewest possible turns. This is why autistics often talk for a long time without giving space for anyone else to say anything. We want to get everything out in one turn. We also may look at interacting as having two roles: the communicator and the listener. The roles don’t switch back and forth within the interaction. Trying to figure out at what point in the interaction the roles are supposed to change can be really tough, or even impossible for us. We also have Economy of Communication. Through a pretty impressive analysis of what we need to communicate and who we are communicating it to, we will use the mode or modes of communication that will take the least amount of effort. This is because all communicating is pretty taxing for us, even when we enjoy it. If we use the fewest possible resources to communicate something, we are more likely to have enough resources left to communicate something else later. By saying fewer words now, we will have more to use later. We say less because we want to communicate more. If a gesture will work, we can save even more words. If we can borrow words using echolalia or scripting, we get to save our own. Maybe we only have 30 circles of communication to use in a day. If someone purposely makes us use them all at once, we may not be able to commuicate something really important later. I’m passionate about access to communication for everyone. I fought for our public school system to provide my child with an Ipad loaded with an AAC (Alternative and Augmentative Communication) app that can hold up to 14,000 words. I want my child to have access to any word he may one day want to use, and I work with him every day to increase his expressive and receptive vocabulary by modeling multiple modes of communication, including AAC, oral speech, laminated pictures, ASL, echolalia, gestures, and music. We declined the services of the speech therapist who wanted to expand his circles of communication to 30 over the course of a year. My job is to give my child the access to communication tools and support in learning to use them. To give him his own voice. It is not my job to decide how he will use it. That’s his journey. I trust him to know what communication stratagies will be most effective for him in any given situation. I will continue to do everything I can expand his options, and I will reflect on how cool it is to watch my kiddo experiment with these options, putting the pieces together to craft a style of communication that is uniquely and authentically his. *One of the dictionary definitions of economy is “careful management of available resources”. Joint attention is a developmental skill. Therapists and evaluators and special education teachers throw it around all the time, test for it, mention it in their reports and education plans. Joint attention is the ability to do something with someone else. So, if you read a book to your kid and they look at the book, look at your face, and appear to be listening, that’s joint attention. If you read and they run around the room doing their own thing, or play with toys across the room without acknowledging you or the reading, there is an absence of joint attention. Another example is responding. If i say my child’s name and he typically responds, he has demonstrated joint attention ability. If he generally does not respond to his name after a certain age, his joint attention ability is considered delayed. In neurodivergent (that’s a word that means non-neurotypical, if you didn’t know) children, joint attention is often delayed. In autistic kids—particularly autistic kids with complex communication needs (CCN)—joint attention is often framed as a social skill that must be acquired in order to learn communication. So, hey. Let me hit pause for a second. We might not know each other. Maybe you’re my real life friend, maybe you’ve seen my comments in passing in a facebook group, or maybe you found your way here randomly. Either way, I think you should know my stance on autism real quick before we go further. I believe autism is a natural, neurological varience in human beings that has always existed. I do not believe autism can or should be treated or cured. I believe in the social model of disability—that it is lack of access and support for disabled people that is disabling, so disability solutions should be centered around increasing access and support, not “fixing” the disabled person to be better able to function in inaccessible and poorly supported situations. I’m into a strengths-based frame when it comes to autism. And by that, I don’t mean “Yes, she’s autistic, but she’s so sweet/cute/funny/caring.” Sweetness, cuteness, being funny, and being caring are not specific strengths of autistic neurology. Some actual strengths of autism are pattern recognition, information proccessing, attention to detail, memory, ability to collect and organize large bodies of objective knowledge in areas of interest, and implicit and lateral learning. I believe that autistic children should be given opportunities to use and further develop these strengths, not just in addition to, but sometimes *instead* of strengths associated with neurotypical neurology. Basically, there’s some stuff us autistic people are *really* good at, and some stuff we suck at. In general, let us do the stuff we’re really good at, and—unless there’s a good reason not to—let us skip the stuff we suck at. In my “strengths” list up there, I mentioned implicit and lateral learning. Autistics are often much better at implicit learning than explicit learning. That means we rock at teaching ourselves things, and have difficulty with someone else teaching us. The lateral part means that we do better when learning activities, people, and materials are kind of off to the side, and we get to control what makes it into our direct line of sight (or what slivers we let in with peripheral glances. Ever see your autistic kid glancing at something our of the corners of their eyes? Know what they’re probably doing? Controlling the amount of stimuli they’re taking in so they can keep up with processing. Brilliant, right?) Face to face learning doesn’t work well for autistics most of the time. Too overwhelming. We have to use up so much of our brains just processing sensory information, so there’s not much brain left to learn with. So, back to joint attention. Are the dots in your brain connecting? If autistic people tend to learn better in the absence of joint attention—doing better with implicit and lateral learning—why would joint attention be considered an important tool for learning communication? That’s, like, kind of nonsensical, right? Put someone in a situation where they can’t learn well so they can learn better? Yeah, they don’t mean that joint attention is nessesary for communication development. They mean joint attention is nessesary for *typical social* communication development. Typical, meaning neurotypical. Meaning, not autistic. And yeah, if you want a kid to sit across from their classmate and look them in the eye and play an imaginative game with them that includes taking turns chatting, they need joint attention. But, we suck at that stuff. Not our wheelhouse. In many cases, we’d really rather skip it if there’s not a reason we absolutely have to do it. Joint attention can be really difficult and draining for us. Now, I’m not saying no autistic person should ever be supported in increasing their joint attention ability. Sometimes there is a good reason. There are times when joint attention is nesessary for access and safety. I can take my kiddo out of his stroller a lot more often if he’ll respond to his name when I call it. That’s enough of a reason to work on increasing joint attention in that kind of scenario. Also, sometimes experiencing joint connection with caregivers can deepen the attachment bond for both caregiver and child, and while I don’t really think it’s fair for parents to have expectations around joint attention with their autistic kids, I think it’s fine to soak them up when they occur naturally. As far as a social skill to be generalized across people and settings, though, I think we need to shift our focus to valuing parallel play, and that awesome implicit, lateral learning over joint attention with autistic learners. Not only do we need to accept it, we need to understand that it actually allows autistic children to optimize their learning, including learning about communication. Finally, I need to say that there are no prerequisitcs to learning to communicate. Anyone who says joint attention is required for development of commication needs to update their research. But that’s another post for another day. Tonight, Mischa was throwing the big green playground ball up, delighting Foxy.

For over a year now, Foxy has been enamored with gravity. He will bring you things to throw. Not just balls. Water bottles. Shoes. His big plastic toy barn. He will place the item in your hands, often arranging your grasp to his specifications, and then nudge your hands up, indicating he expects you to throw the item. Once you throw it up, catch it, and repeat (ad infinitum if he had his way), he jumps and flaps and displays lots of pleasure and excitement. Mischa posted a video of this on his facebook once, and a commenter responded with, “I hope that sometime in my life I feel about something the ways your kid feels about physics”. So, this was playing out tonight with the big green playground ball. Mischa stopped throwing at one point, and Foxy, for the first time, spontaniously signed “up”. I got excited. “Mischa! Mischa! Did you see that? He signed up!” Mischa began throwing the ball again (one of our operating procedures is “respond to all communication”), now exuberantly saying “up!” each time he threw the ball. Foxy loved this, and after a few rounds he said an aproximation of “up” using oral speech. That was also a first, and Mischa and I were delighted. And then it happened. As I sat nearby watching this amazing, connected moment unfold, I thought, “Is there a way I can expand the theraputic value of this interaction?” So, this is a thing. When you have a disabled kid who needs extra or atypical developmental supports, you can get into this mindset that every moment has theraputic potential, and the goal is to maximize as many of them as possible. At this point, we don’t outsource very much developmental support. Foxy gets 30 minutes of private speech per week (we just cut down from 60 minutes), and a couple weekly early intervention home visits. We had a private OT evaluation recently, with 120 minutes of private OT recommended in the report, but we decided to opt out for now. Foxy has a sensory gym at home, and we use the equipment with him daily. Mischa and I guide his development ourselves, for the most part, which means I spend a lot of time researching. Doing all that research can really reinforce the “mazimize every moment” frame. There is so much that can be done to support our kids’ development, after all! Why wouldn’t we pounce on every opportunity to provide meaningful support that could give them better, brighter futures with more options? Because—and I am just going to say this definitively—that’s no way to live. No way for me to live. No way for Foxy to live. Foxy is precious, beautiful, and—like all humans—has inherant value because he is here, alive. It is a mean trap to fall into, the idea that I need to go above and beyond general good parenting to fix or build or reveal something in him so he can have a bright future. His future is bright because he has loving, supportive people in his life who will advocate for his access to it, and teach him to be a self-advocate. The threats to his future’s brightness are the ableist structures and systems and people who will try to limit his access to it. Not the fact that I could have modeled more multimodal communication while Mischa threw the ball tonight, but chose to just enjoy the moment instead. If our relationships with our kids becaume centered around fixing them, our children will start to look like problems to us by default. Fixing is for problems, after all. They do need us to recognize, though, where they need supports, and we are entrusted with providing those supports and teaching our kids to access them. This parenting work can creep into the realm of “fixing” sometimes without us immedietely seeing it. It can also begin to dominate our relationships with our kids. In my experience this has felt really good, until sudeenly it doesn’t. The pressure to preform builds up until even thinking about playing with my child feels stressful. I’m still designing my checks and balances with this element of my life. When parents have a toddler with a new autism diagnosis and ask for my opinion on what they should do for their child now that they have this information, I almost always tell them to spend a few months just focusing on their relationship with their child before deciding about any therapies or interventions. Really connect. Make sure that bond is solid, that there is trust and security for the child. Whatever a child’s development holds, the best way to maximize it is to give them the certainty that they are loved an accepted unconditionally by their parents and caregivers. So, I will take my own advice. I will maximize connection. I will maximize space for authentic interactions that respect my child’s neurology. I will maximize the messages of acceptance and love I give my child. I will maximize the delight I experience just watching him move through the world, without expectations. I will maximize opportunities to respond to his emotional needs with my full attention, and with compassion and curiousity. And when he is laughing and jumping and flapping as my partner thows the big green playgound ball for him, saying and signing “up”, I will not wonder if I should grab the talker and model UP, or whether I should be modeling the sign so he’ll maybe do it again, or if I should instruct Mischa to add an expectant pause before he says “up” as a way of prompting Foxy to say his aproximation again. I will maximize how good it feels to be with my family in this moment where Foxy was so happy that he just had to find a way to tell us about it. |

I’m an autistic mom with a neurodivergent partner. Together we parent two autistic kids and herd five cats.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed